The First Encounter

Soon after moving from Beijing to Hong Kong in 1979, I spotted a stamp convention ad in a newspaper one day. Intrigued by the notion that my idle hobby could possibly merit any kind of gathering, I decided to stop by in the hopes of meeting fellow teenagers who shared my interest in peeling off staid little pictures of Queen Elizabeth and Franklin D. Roosevelt from mail that came in from overseas.

On a hot and humid late afternoon, with an album tucked under my arm, I marched into a hotel near the Central, the downtown area, where the convention was being held. I thought about my stamp friends back in Beijing as I passed through the hotel door into the cool, air-conditioned lobby. We used to compare and exchange stamps in the classroom and playground. Back then, China was a poor and dreary place, and my friends had to use cheap softcover notebooks to keep their stamps in one place. But my album was a gift from my grandfather Yeye. Although the four corners were all well-worn, it was a unique luxury and I even got few tempering offers for it. Its contents were the most coveted, because China’s self-imposed isolation made those colorful foreign stamps rare commodities.

The Central. 2018.3.27, 10am. The Maritime Museum exhibits remnants of a Yankee who fought for China in the first Sino-Japanese War in 1894.

The concierge at the hotel gave me directions to the ballroom on the fourth floor. I saw a few middle-aged men in suits pacing the hallway as soon as I stepped out the elevator. That should have tipped me off that the convention was for grown-ups, but it didn’t register. Looking out to my far right, I found the ballroom. One of the heavy double doors was ajar. A man, a convention goer I suppose, in front of me opened it wider and held it for me. The sound of hushed chatter washed over me. The high-ceilinged ballroom contained more businessmen in dark suits standing among rows of glass display tables. The austere-looking crowd milling about beneath a Victorian chandelier immediately took me aback. I was stunned, disappointed. Feeling totally out of my depth, I wondered, “What did I get myself into?”

“Come on in, please,” said the man holding the door with bemusement, as if daring me. There were a couple of men behind me on their way in. “Fine,” I said quietly. Taking a deep breath, I went in, and felt even more daunted once inside, unsure of where to stand or even of how to carry myself. I put my head down, pretending to inspect a display near the entrance while trying to find a way to escape, unnoticed.

“Is that your collection, miss?” A baritone voice rose from behind me. I turned around to face a respectable gentleman in a well-cut blue suit.

“I’m John.” He said.

“Errr… collection?” I frowned. “Yes, your collection.” He nodded toward the little album tucked under my arm. “Oh yes, I collect stamps that are hard to find and are very pretty,” I said. I was unsure whether or not my album actually qualified as a collection, but was nevertheless flattered – and relieved to have someone to speak to.

“May I see it?”

“Oh, sure.” I was more than happy to show off, and grateful for being saved from total awkwardness.

John pushed up his black-rimmed glasses, and flipped it open to reveal my rag-tag “collection”, accumulated from years of correspondence with overseas relatives, plus a few pages of colorful foreign chocolate wrappers. Stamp collecting was a loosely-defined hobby for me that extended to chocolate and candy wrappers because their foreignness made them seem just as rare and exotic as some stamps.

“I see, very interesting.” He smiled and asked me to join him for a drink.

We found seats in the darkwood-paneled lounge by a window that overlooked Victoria Harbor. The Kowloon Peninsula could be seen in the distance. The tropical sun was beginning to set, casting a golden hue on the little sampans, sailboats, flat barges, stocky ferries, and ocean liners that filled the waterway just a few floors below us. He ordered a Johnny Walker for himself and a Campari and soda for me.

“So, what made you want to collect stamps?” John asked. I tried hard to come up with a sophisticated response. When I failed, I confessed truthfully and with much sheepishness, “Mmm… I was attracted to the pretty designs.”

Much to my surprise, he replied, “Oh, that’s very common. Zhou Jinjue…” he began, before pausing, carefully considering his next few words. “… Zhou Jinjue started the exact same way as you did, from this worthless foreign garbage.”

Zhou who? I had never heard of him, but he obviously regarded him with importance.

“Is he at the convention?” I asked.

His laugh resonated across the room.

“The King of Chinese Philately? No, he passed away three decades ago, long before you were even born.” He then proceeded to lecture me on the value of the stamps that all the dark-suited men had come to discuss, debate, and exchange. He spoke of single stamps that held astronomical value, and how counterfeiters went to extreme lengths to replicate them. I had just received my first lesson in the philatelic arts and I was smitten.

After downing our drinks, he casually asked, “Do you like history?”

“No,” I answered bluntly. History was for old people with wrinkles! It was a simply dreary subject that I had to suffer through in school. Despite my stilted views and glaring ignorance, he offered me an apprenticeship. As he described the job, my eyes lit up: someone would actually pay me to sort out these scraps of paper?

The Talk of the Town

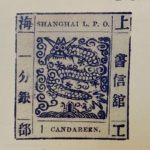

Shanghai Large Dragons by Dr. Wei-liang Chow

On my first day of work at John’s import and export office, he brought out bags upon bags of stamps that, to my inexperienced eyes, looked very dry and dull. Where were the flashy scenery and striking butterflies? I balked when I spotted the Shanghai Large Dragons with their distinctively unperforated edges. Freshly armed with the knowledge that there were stamp forgeries, I wondered whether the counterfeiters had forgotten to finish the job due to lack of equipment or time. “Aren’t they fake?” I blurted out confidently. The silence that followed was deafening. The three cheerful employees with whom I had just been acquainted with quickly hid behind their desks and hunkered down behind their piles of work.

John laughed. “No, there are different kind of stamps. Actually, the son of the King is well-known for collecting these kinds of stamps.”

I suppose my first job was not the bargain I had hoped for, but I soldiered on for the simple reason that it financed my Italian shoes and handbags. John was fond of regaling me with anecdotes and lectures on history, most of which fell on deaf ears. However, I retained the stories about the King and his role as the founding father of Chinese philately. As if to reinforce those lessons, he resurfaced as the talk of the town in 1982, when the Holy Grail of Chinese stamps, the 1897 Red Revenue “Small One Dollar” block of four (dubbed simply the Block of Four) was acquired by Lam Manyin from Allen Gokson’s estate at an unprecedented price of $280,000 USD. The King had obtained this rarity from its original owner, de Villard’s widow in 1927, but was forced to sell it twenty years later to Gokson for $20,000 USD to finance the payoff of a bribery. This dethroned him as the Stamp King, and he ultimately passed away a few years later with a broken heart and without ever having redeemed himself.

Then, a year later at the Chinese Classic Stamp Exhibition in Taipei, the new owner of the Block of Four generously lent it to be displayed in public for the very first time. Predictably, this caused considerable excitement among knowledgeable philatelists. My mentor and his fellow collectors made the pilgrimage to Taipei to see it. I had not been in Hong Kong long enough to gain a tourist visa due to the strained relationship between the Straits, but was more than happy to stay behind minding the fort.

Alas, John’s exuberance at having finally seen this “rarest piece of stamp in the Eastern Hemisphere” in-person soon subsided. Mrs. Margaret Thatcher went to Beijing to sign the agreement that would surrender Hong Kong to China come 1997. It was a death sentence even back in the 1980’s, without knowing how much further China would fall. Iron Lady Thatcher’s signature instantly spoiled the boastful spirit of the Hong Kongers. John’s business trips to Manila and Shanghai became more frequent, escorting Chinese officials. After getting me a Filipino passport to settle a debt with me, we lost touch. I sold my small collection to a Swiss enthusiast, moved to Europe for a few years. By the time I settled in New York in 1986, philately was the furthest thing from my mind.

The King and I

I was born in Beijing as an only child. My parents met in the 1950’s at the basketball court in Jingshan Park. It was only a stone’s throw away from my home and the Forbidden City. My father captained the army team Katyusha for which my mother played forward. When the Cultural Revolution came crashing down, their military tenure proved insufficient to write off their bourgeois backgrounds. Mother was incarcerated, and she committed suicide four months later. It was the spring of 1968 and I was just about to begin first grade in the fall. The intervening years were very tough for me, especially when Father decided to pass me off to our relatives. The frequent uprooting and disconnecting kept me in the dark about my background. More importantly, Mother’s suicide had political overtones, so no one dared broach the subject of family with me around. For the sake of survival, the greater the distance from politics, the better.

After my children were born in New York, my sense of family steadily developed, and my desire to learn about my roots grew stronger. As if on cue, in November 2000, my grandaunt Lucy sent me her memoir, providing me a rare opportunity to peek into my genealogical past. I became determined to research my mysterious ancestry and piece together a family tree.

The New York Times had spent the entire summer of 1895 covering the anti-missionary riots in Sichuan and Fujian. One of my great-great-grandfathers was the Viceroy of Sichuan and was identified as the instigator. The British issued an ultimatum: The Royal Navy would intervene unless he was punished. When a British fleet of four large gunboats appeared in the waters of Wuhan, the Emperor caved in. Another great-great-grandfather, Zhou Fu, was described by the New York Times: “He … is able and progressive and has pro-foreign views.” His son would employ a 24-year-old engineer named Herbert C. Hoover, who eventually managed to wrest away the mine during the chaos of the Boxer Uprising. The Emperor sued for justice, but lost the case in London. Needless to say, my indifference towards history began to shift.

Chinese Intellectuals and the West, by Y.C. Wang

A few years into my research, one day I decided to reward myself with some quality time at the local library — no agenda, no checklist. As I strolled down one of the aisles, a black book with a baby pink stripe on its spine caught my eye. After flipping through a few pages, I found another long-lost uncle. I immediately raced to the computer and Googled him.

Chow Weiliang (1911-1995) was an authority on algebraic geometry. His main gig had been to chair the Department of Mathematics at Johns Hopkins University. He held that position for more than a decade before retiring in 1977. The finding boosted my spirits. Eager to place him on my tree, I waited twelve long hours before calling Uncle Zhou Weizeng (Junliang, 1920-2014) in Tianjin, the de facto patriarch who had written many books about our family.

“Uncle, do you know Weiliang?” I called as soon as the pendulum struck ten in the evening, our usual calling time.

“Of course I do. The mathematician. He’s from da fang.” “Fang” refers to the male branch of the family. Weiliang’s branch is from oldest son, and Weizeng’s is from the youngest.

“How come you never mentioned him before? How many others have I missed?”

“Well, there are so many, I could not possibly remember them all.” He chuckled softly. “Have you looked up Kaoliang?”

“Yes, I did. He passed away in 1998.” Chow Kaoliang (1918-1998) was a pioneer neurobiologist. I found his memorial on Stanford University’s website.

“Hmm… that sounds about right.” I could hear him wracking his memory for more bits of information. He then continued, “You should remember Weiliang’s father, Zhou Meiquan, who was a famous mathematician himself. I mentioned him before.”

“I do remember, Uncle.” He was already hanging on my tree, listed as a poet and mathematician.

“He was famous for stamps too.” Uncle Weizeng continued. I perked up. I knew many ancestors were famous collectors of various objects. But at the beginning of my research, I was inexperienced and overlooked these idle preoccupations as typical social trappings.

“He used to own a very rare stamp, something called “one dollar” — you know, four stamps connected together. He died after selling it with a broken heart.”

By now, I was only half-listening as my mind started to race.

“Did he go by any other name?” I was less green now that I at least knew how to ask the right questions.

“Of course. He’s commonly called Zhou Jinjue.”

Apparently, he is known as M.D. Chow in the West, Zhou Jinjue in the Chinese philately community, and Zhou Da or Zhou Meiquan by family.

My tree had borne new fruit. I basked in the irony that this Renaissance man, of whom I had heard so much during my ignorant youth, turned out to be an important part of my familial heritage.

A few years ago, I learned that Lam Manyin sold the Red Revenue block of four, along with one other sheet in 2009, to a Shanghai property developer for a reported $18.8 million in a private deal.

I was right about one thing: historians are octogenarians by nature. And now that I’ve got wrinkles of my own, history will never pass me by again.

Zhou Jinjue’s son, Wei-liang Chow, or Ed, which was commonly used by his friends and colleagues, was an authority on the Shanghai Large Dragon stamps. His book (ISBN 962-7287-27-X, on Amazon) was published by Hong Kong Pressroom in 1995. Charles W. Dougan, FRPSL wrote in the Foreword, “Dr. Wei-liang Chow was a profound student of Chinese philately and had a special interest in the stamps that postal history of the Shanghai Local Post going back to his days as a youth living in Shanghai.”

Zhou Jinjue’s son, Wei-liang Chow, or Ed, which was commonly used by his friends and colleagues, was an authority on the Shanghai Large Dragon stamps. His book (ISBN 962-7287-27-X, on Amazon) was published by Hong Kong Pressroom in 1995. Charles W. Dougan, FRPSL wrote in the Foreword, “Dr. Wei-liang Chow was a profound student of Chinese philately and had a special interest in the stamps that postal history of the Shanghai Local Post going back to his days as a youth living in Shanghai.”